-

Change society, not (only) infrastructure!

An essay I wrote for the “Unraveling the cycling city” MOOC of the University of Amsterdam

-

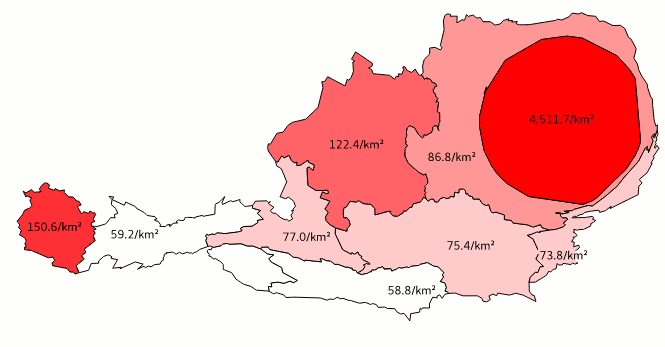

Cartogram Plugin for QGIS3

I rewrote a popular plugin for QGIS3 -> better performance, more features

-

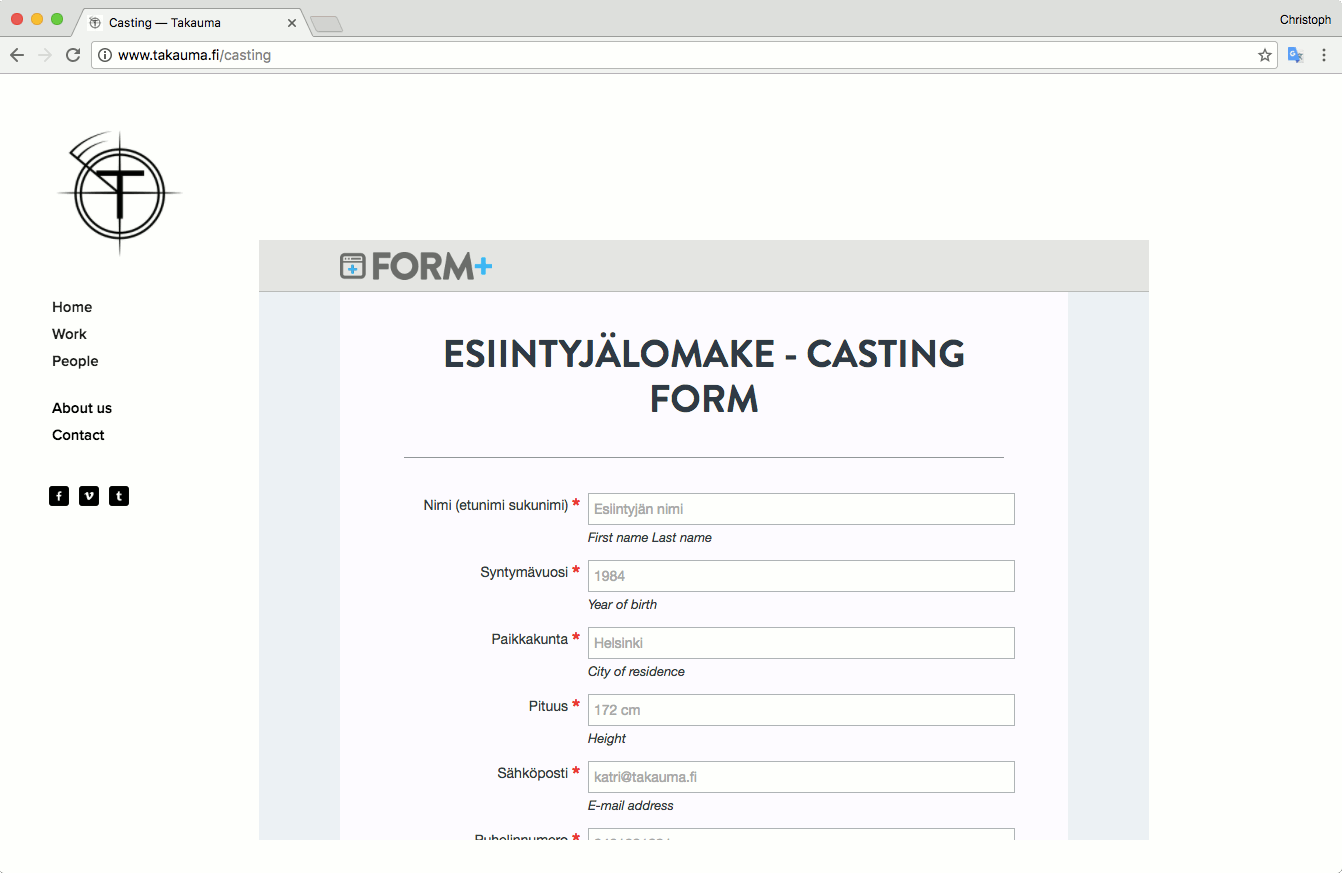

Helsinki Street Casting: a Google Apps Script love story

Uploading directly to Google Drive and Spreadsheets

-

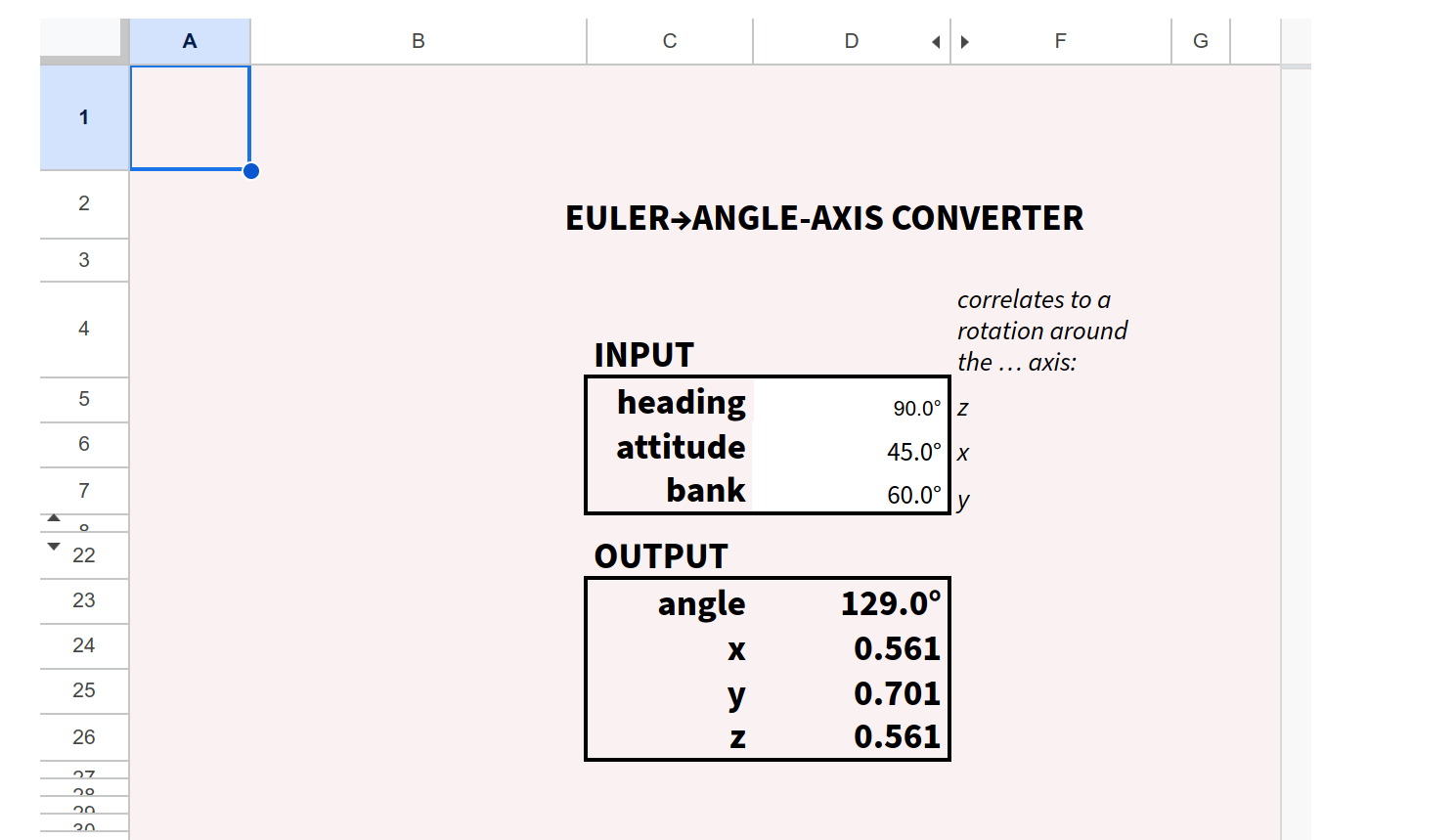

Euler to Axis-Angle converter

convert 3D component rotations to an angle-axis representation

-

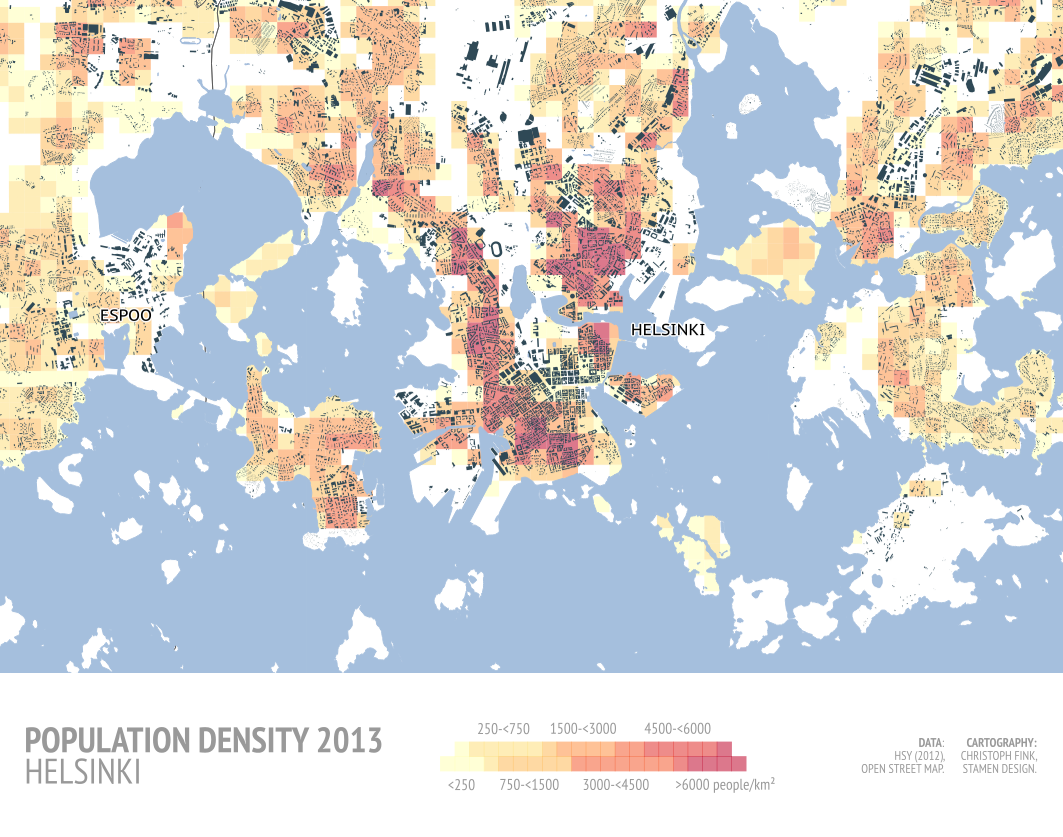

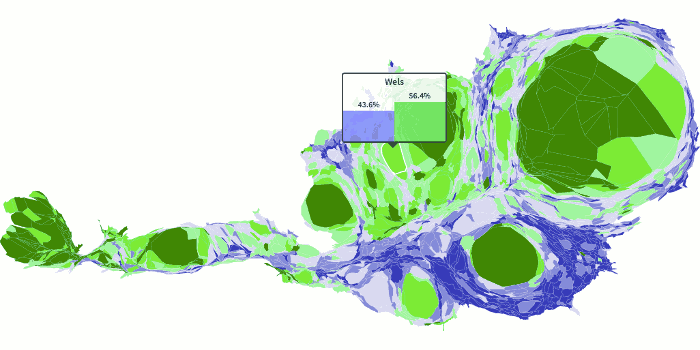

austromorph.space

anamorphic maps to represent Austria’s social topography